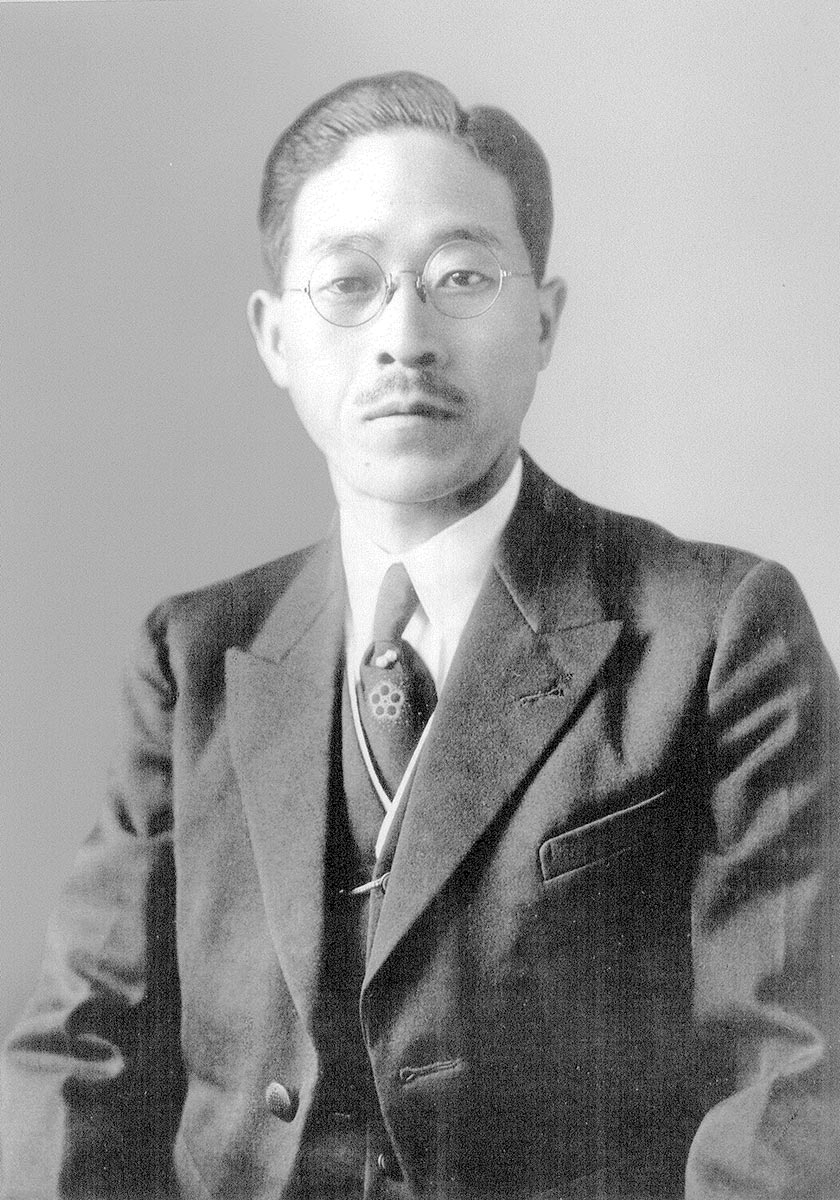

Founder, Shiro Arimoto

Nurturing engineers who learn from society and contribute to society

SIT’s predecessor school was founded by Shiro Arimoto in 1927. Since those early days, SIT has remained committed to a practical approach in educating and nurturing engineers. Its founding philosophy is firmly rooted in this legacy.

Shiro Arimoto advocated “education in which the various aspects of modern culture are incorporated in the curriculum to help students learn the significance of contributing actively to society.” SIT’s practical approach to education has enabled it to nurture engineers with the practical knowledge and skills necessary to support a technology-oriented country. This, together with its ability to produce outstanding engineers possessed of both a strong sense of ethics and comprehensive knowledge, has underpinned SIT’s long-term contribution to progress and development in society at large.

Up to the present day, the education SIT provides based on its founding philosophy has continued to result in competent professionals; its graduates are widely regarded as capable and dependable engineers.

Shiro Arimoto advocated “education in which the various aspects of modern culture are incorporated in the curriculum to help students learn the significance of contributing actively to society.” SIT’s practical approach to education has enabled it to nurture engineers with the practical knowledge and skills necessary to support a technology-oriented country. This, together with its ability to produce outstanding engineers possessed of both a strong sense of ethics and comprehensive knowledge, has underpinned SIT’s long-term contribution to progress and development in society at large.

Up to the present day, the education SIT provides based on its founding philosophy has continued to result in competent professionals; its graduates are widely regarded as capable and dependable engineers.

SIT’s Founder, Shiro Arimoto

Shiro Arimoto graduated from the University of Tokyo’s predecessor school in 1923, having worked to support himself through his education. He went on to study economics, reenrolling as an undergraduate in the economics faculty at the same university. Eventually his passion for learning led him to study law, literature, and commerce, in addition to engineering and economics, and he obtained a total of five bachelor’s degrees. At only 30 years of age, while a graduate student, he founded the school that would become SIT.

Dr. Shiro Arimoto

Dr. Shiro ArimotoIn Memory of Founding Father "Shiro Arimoto"

Shibaura Institute of Technology: Weaving 80 Years of History In Memory of Founding Father “Shiro Arimoto” Misako Arimoto Henson

On November 4, the venue for the 80th Anniversary Ceremony of the Shibaura Institute of Technology was enveloped by deep emotions created by the speech by Misako Arimoto Henson, the third daughter of Institute Founder Shiro Arimoto. Speaking in front of the image of her father projected onto the massive screen on the stage, and wearing the kimono left by her mother Yoshiko, Ms. Arimoto spoke to the audience as if to reach out to them as one with her parents. So moved by her speech the audience kept clapping for a long while after she delivered her last words.

Thank you for inviting me to the ceremony today. And it is my deepest pleasure to be able to speak about my father on this occasion.

I was born in 1937 as the last of five siblings. My father passed away in 1938 at the age of 42, so I don’t even remember his face.

All I know about my father mostly came from what my mother told me. My mother become a widow at the age of 32 and did not remarry. She died at 73 around 30 years ago.

I was born in 1937 as the last of five siblings. My father passed away in 1938 at the age of 42, so I don’t even remember his face.

All I know about my father mostly came from what my mother told me. My mother become a widow at the age of 32 and did not remarry. She died at 73 around 30 years ago.

Shiro Arimoto(The center of the front row)

Shiro Arimoto(The center of the front row)I think that to my mother Shibaura Institute of Technology represented my father himself.

Thus, I came today wearing my mother’s kimono so that I am with her speaking to you about my father.

Thus, I came today wearing my mother’s kimono so that I am with her speaking to you about my father.

Just like myself, my father lost his father when he was one year old. According to the traditional family system before the War, his young mother was forced to go back to her parents’ home, parting ways with her children. My father never saw his mother again.

As his name suggests (“Shi” in “Shiro” has the same pronunciation as the Japanese word for number four), my father was born as the fourth son. In those days, a common idea was that children other than the first son did not need education, unless the family was wealthy enough to afford their education. My father wanted to continue schooling after primary education but was not allowed so he ran away from home.

While working as an apprentice, he taught himself to sit for the national examination to receive a qualification equivalent to a junior high school diploma. Right before the examination, however, he got typhoid that was prevalent at the time. He wrote home a letter in English asking for help. One of his elder brothers, who was able to read English, came to his rescue. Then, they began living together, with my father’s brother working to support the education of my father. Also with some financial assistance from a charitable person in his home province, my father was able to enter the Seventh High School (one of the prep schools feeding the Imperial University of Tokyo) and moved on to study at the highest institution of learning, Imperial University of Tokyo. By the time he entered the university, he was three years older than his peers.

It is said that my mother was a beauty and in her youth she was called the “Beauty of Hongo.” (Hongo is the place where the Imperial University of Tokyo was located.) The parents of one of her best friends owned a bookstore in Hongo, and my mother became acquainted with my father who was frequenting the bookstore. They eventually got married. Apparently, my father could not afford books and was there all the time.

My father had a small frame, partly because he went through hard times and he didn’t have good nutrition when growing up. And he was always wearing the same old black cape and got the nickname “Crow.”

My mother was attracted to my father’s resilient spirit and noble ambition, and decided to spend the rest of her life with this penniless student. My father was 29, and my mother was 19.

My mother was attracted to my father’s resilient spirit and noble ambition, and decided to spend the rest of her life with this penniless student. My father was 29, and my mother was 19.

Misako Arimoto Henson

Misako Arimoto HensonSince the Meiji Restoration my mother’s family was running a small factory making precision machinery for Seiko (watch maker) located in Honjo in Sumida Ward. It was a typical, traditional cottage industry with the apprenticeship system like everyone practiced at the time in Japan.

My father declined the offer from Mitsubishi Company and reentered the Imperial University of Tokyo majoring in Economics. While continuing his study, he worked as a lecturer at Iwakura Railroad School (current Iwakura High School) at night. He found fostering of engineering education his mission and was preparing to answer his calling, which was to establish and run a vocational school.

Having worked as an apprentice himself, my father reportedly believed in the need for vocational schools in Japan to provide students with the necessary education to make their living after graduation.

First, he founded a school in Osaka specializing in commercial and industry education, but it didn’t work out. After my father went to Tokyo to secure needed money my mother was left alone in unfamiliar land with her newborn baby. She frequented a pawnshop to get by and ate only a piece of tofu a day to survive month after month while waiting for her husband to come back not knowing when.

Fresh out of school and having no money, my father, 31 at the time, had the unthinkably bold ambition of opening a new school. It was his strong conviction of the absolute need for a certain type of school for the future of Japan. It was his burning desire to realize his educational ideal, and his confidence towards efforts gained through overcoming many years of hardship, that led my father to take on such a major enterprise that no ordinary person would ever think of it.

My father firmly believed that the quality of its faculty would determine the success of a school. Based on this belief, he poured his brimming enthusiasm and his tenacity persuaded others to come to his school to teach or to help him with funds. His selfless love for his country and society moved people and led to success. Also in order for working people to study to get a better career, my father decided to offer night classes and set up his school in Shibaura area having an easy access to business areas in Tokyo.

My father firmly believed that the quality of its faculty would determine the success of a school. Based on this belief, he poured his brimming enthusiasm and his tenacity persuaded others to come to his school to teach or to help him with funds. His selfless love for his country and society moved people and led to success. Also in order for working people to study to get a better career, my father decided to offer night classes and set up his school in Shibaura area having an easy access to business areas in Tokyo.

Misako Arimoto Henson

Misako Arimoto HensonMy mother always described my father as a “person who was born a little ahead of the time.”

His love for learning prompted my father to graduate with a wide range of major from engineering, economics, and law to commerce and literature, 5 BAs and 1 MA from two Universities. However, I was told that there were also unfavorable characterizations of my father as a jack-of-all-trades, someone too keen for “titles,” and businessman playing the stock market and running side businesses–even though the purpose was to raise money for the school.

My fathers had un unceasing curiosity and a very competitive nature. He took interest in everything and gave his 120 percent to whatever he did to live his life fully. I remember my mother saying, “When a person is born, God has already decided what the person is to accomplish in his or her life, and probably your father achieved his duty by the time he was 42 so God called him back”

The Institute is now celebrating its 80th year since founding, and a new campus has just opened in Toyosu. It has grown into a fine institution, offering an integrated educational program encompassing junior high school, high school, university and graduate school curriculums. For that, I sincerely thank all those who succeeded my father and helped achieve my father’s dream.

Looking back on the Institute’s 80 years of history, I must say that my parents’ involvement was very

When looking back on the Institute’s 80 years of

history, my parents’ involvement was very brief.

The school existed only 11 years at my father’s death, and until the years my mother physically donated the school to establish it as a public entity [Shibaura Institute of Technology] in 1943, my parents were involved in the Institute for no more than 15 years or so.

Therefore, during the Institute’s long history, there was a time no one knew about its founder. Now, my father is being remembered and being honored, Further more the founding spirit of my father is being revived, and recognized. And I believe the person who is the happiest to see it is my mother in heaven.

I went to the United States in 1964 and settled down in Torrance, a suburb of Los Angeles. I’m now a U.S. citizen and contributing as a member of my community. Five years ago, I had the honor to receive the most prestigious award given to those who devoted their life to the betterment of the community by the City of Torrance.

In 1972, I visited Kashiwa City in Chiba Prefecture as a representative of Torrance to establish a sister-city relationship between the two cities. About that time I heard that coincidentally the Shibaura Institute also began talking to Kashiwa City as a potential location to move the attached high school to Kashiwa. The late Mr. Hideo Naito, who was instrumental in the relocation of the high school, was a resident of Kashiwa and also a member of the editorial committee preparing for the 50th anniversary publication of the Shibaura Institute of Technology. Looking for information about the Institute’s founder, Mr. Naito contacted me in the U.S. through a Kashiwa City official and I provided him with a book of my father’s bibliography, which survived through the war.

It was this 50th anniversary publication that made the name of my father officially known as a founder in the institute. I am awed by the wondrous power behind these chance events and encounters. I have particularly strong feelings toward my father, probably because I didn’t know him personally. Or, I may have inherited the strong affection for the Institute from my mother.

When my father was unknown as a founder of the school, I was still a young student growing up in Japan. However, I already had this dream of setting up a scholarship in the name of my father.

To commemorate the 80th anniversary of the Institute, I decided to fulfill my long-held dream and established the Arimoto Memorial Foundation within the University of California (having 10 campuses in California) in the US for the benefit of Shibaura Institute of Technology.

I am just a simple housewife and not a businessperson, so I cannot do much to contribute in terms of my monetary abilities. However, it is said the lantern of a poor person is bright as 10,000 lanterns of a rich person. I made the decision to set up the Foundation by believing that doing so is the best way for me to answer and repay my father’s passion and my mother’s love.

Also by this action if I can show the gratitude and return even a small favor to the many faculty members past and present who have helped this Institution to grow into such a big tree from the seedling my father had planted and nurtured by putting his heart and soul together with my mother.

I hope that this Foundation will be of some help to the Institute as it expands internationally and becomes a school every faculty member, student and graduate of the Institute will be proud of.

New research by Dr. Tsuyoshi Maruyama, resulted in revealing the fact that coincidentally the Shibaura Institute of Technology celebrated its eighth anniversary on this day in 1933 following the completion of its new campus building.

In the school newspaper, which Dr Maruyama discovered recently, my father explained the reason why the Institute celebrating its eighth anniversary, without waiting for the tenth. He said that the Chinese character for number “eight” is a very auspicious number and had the meaning of “many,” as the character implied and to used in the phrase meaning “multitudinous gods” in the Shinto mythology. He said the number symbolized infinity.

I would like to read some passages from the same article. The following is only an excerpt, so the sentences may not connect sometimes. But I’m reading my father’s words as they were written.

“There is a wise saying, ‘Time discovers the truth.’ At the eighth anniversary of the Institute, I was able to discover the true state of my school.

“We must examine the present, and we cannot reveal where we are at the present without understand the past. And without true understanding of the present state we cannot try to grow the school into the future.

“In general, present day Japan engineers are looked down on and regarded as merely craftsmen with higher skills.

“Belgium, on the other hand, is a nation founded on industrial excellence and those who call themselves an engineer are respected and recognized highly by all classes in society.

“Accordingly, engineers, technicians and all other engineering-related professionals are aware of their mission and responsibility for the nation and have a sense of self-respect and self-regard, and the cream of the crop competes for a seat in every engineering school.

“It is utterly regrettable that in Japan, which calls itself an industrial nation, engineers do not have the same social status enjoyed by their counterparts in Belgium.

“Japan has scarce land and it is obvious that we cannot depend on agriculture to build our nation. Accordingly, it is destined to develop itself as an industrial nation. In this sense, maltreating engineers who will play a central role in the future development of the country is the same as destroying our lifeline.

“Also, for Japan to survive the economic war on a global scale which will certainly become increasingly fierce, its weapon must be the ability to make quality products with less labor and capital at lower cost, where the degree of ingenuity will determine the success. Fostering ingenuity means that we must have very different ideas from conventional thinking.

“In essence, now is the time when we are not only developing industries but adjusting the strategy to promoting innovations.

“Despite the pain and difficulty of running our school and the self sacrifice, I must continue to advocate our innovative ideal until it wins the support of public opinions and is finally realized as none other than our responsibility given the current state of Japan.

“Both the educator and educated shall courageously stride forward toward accomplishing their important mission and recognize, even through pain, the need for self-examination and contemplation. At the eighth anniversary of the Institute, we shall not live in the pleasure of the moment, but study and strive further toward making this celebration a step toward finding our eternal significance. It is my yearning to make us a pioneer and beacon of industry in Japan.”

I hope that these words my father wrote 72 years ago will send a time-transcending message that will resonate with you as you celebrate the 80th anniversary of the Institute.

Thank you very much for your kind attention.

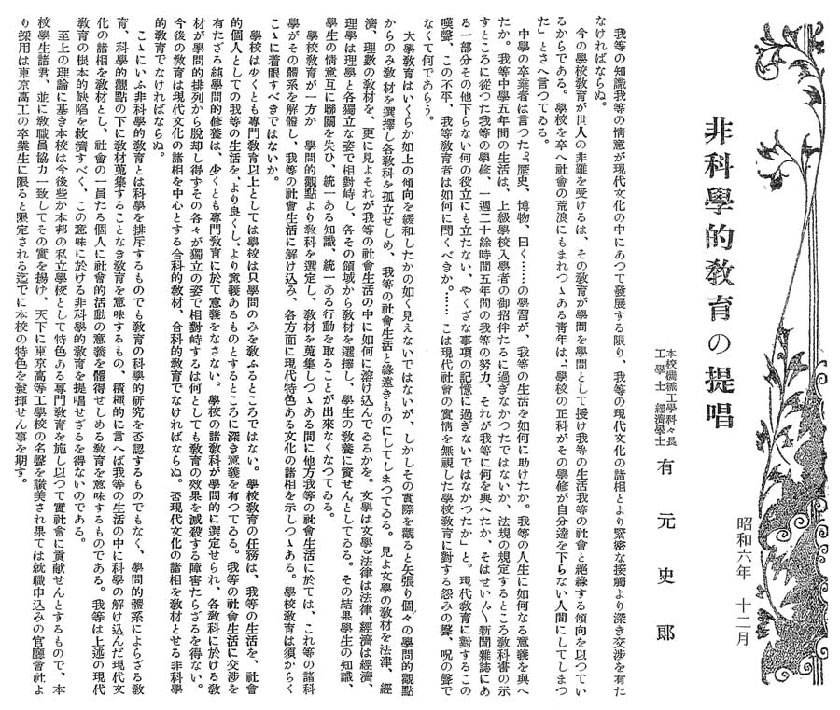

Proposal for Unscientific Educational Approaches

By Shiro Arimoto, Bachelor of Engineering, Bachelor of Economics

Dean of the Engineering Department, Tokyo Koto Kogakko

Founder of Shibaura Institute of Technology

Dean of the Engineering Department, Tokyo Koto Kogakko

Founder of Shibaura Institute of Technology

Published in December 1931

As long as our knowledge and our sentiment continue to develop in conjunction with our modern culture, we must seek closer contact with various aspects of modern culture and maintain deeper relationships with them.

Education in today’s schools has been criticized by society. The reason is that too much focus is given to academic learning that is completely isolated from our everyday life and society. I can even hear young graduates crying out, “School curricula and study based on such curricula have made us worthless beings.” This is the stark realization of young grads after being tossed around in society’s rough seas.

This is a comment from one high school graduate: “How did the school study of history, natural history and all other subjects help us in our real life? What meaning did they add to our life? The five years we spent at high school seemed to me just a period of wasting time because of study along side with students who are advancing to higher education. We studied more than 20 hours a week for five years in textbooks as prescribed by law, but what did we get? It seems only memorization after memorization of worthless, random matter such as almanac, newspaper and magazine articles and others now considered useless facts.”

How should we, as educators, listen to such despair and complaints in regard to modern education? This is none other than an expression of resentment and bitterness against school education, which has been ignoring the actual state of modern society.

University level education seems to be less critical in terms of the aforementioned trend as higher education requires specialized knowledge but in reality somewhat the same thing has been observed. Textbooks are selected simply from the pure academic standpoint, and each subject is taught in isolation from each other in a manner far removed from real social life. Look at them! Look closely at the textbooks for literature or law, economics and science. How are they integrated into our social life? Teaching of literature as literature, law as law, economics as economics and science as science as though there is no applicable connection to real life. Each subject matter remains isolated and textbooks are selected only in the specified field for the purpose of helping students acquire specialized knowledge. As a result, the knowledge and sentiment that students have toward various subjects are not interconnected. Consequently they cannot realize or acquire practical knowledge and take practical action.

Careful observation reveals what is happening in the present day real society. While schools are selecting and gathering textbooks for various sciences from the academic standpoint, these various sciences are breaking away from their original structures and integrating into society, application of sciences creating unique aspects of modern culture that are felt in various quarters. School education should focus on this dynamic.

It is my belief that schools, or at least those that offer vocational training, should not be a place where only academic subjects are taught. The mission of school education is to better our life or improve the way in which we as the members of society live, and to make our lives more meaningful. To me that is the deeper significance of school education. Pure academic training that has nothing to do with real life has no meaning, at least in the context of vocational training.

If various school subjects are selected based on academic reasons only and the textbooks for each subject contain only line after line of academic facts, and each subject segregated from one another then the overall benefits of education will be reduced. Future education must be based on curriculum, which encompasses all subjects, or a combination of subjects, with focus on various aspects of present day culture. Thus I came to the conclusion of proposing an ironic idea, which I call “the unscientific educational approaches,” in which the various aspects of modern culture are incorporated in teaching the subject to be more practical.

Here, “Unscientific Education” is not something that rejects science or denies the scientific method of study. Instead, it means education that is not dependent on the traditional system of academic education in which textbooks are simply chosen from the academic standpoint . To put it more aggressively, this education in which the science and various aspects of our modern culture are blended will enhance each other and every member of society will learn their significance in the meaning of life. By proposing the unscientific educational approaches I would like to revise the aforementioned fundamental defect in today’s education.

Based on the above notion, our school aims to provide unique professional training as a private institution in Japan so that we can contribute to the real world. It is my hope that our students and faculty members will work together to produce great fruits so as to make the name of Tokyo Koto Kogakko (currently Shibaura Institute of Technology) known to the world, so that government agencies and various companies recruiting recent school graduates will be made to think they will only hire our graduates and will proclaim our school’s uniqueness.

Proposal for Unscientific Educational Approaches

Proposal for Unscientific Educational Approaches